MARY ANNE YARDE | Author | Review of Redemption

JAMES GRIFFITHS | Author | Review of Rebellion

Welcome...

My name is Philip Yorke. This is my online home, a place where you

can learn more about my latest books and writing or become absorbed in the world of Francis Hacker, the main character in the series of novels I am writing about the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and the short-lived Protectorate period. In here, you can discover more about the key historical figures of the Seventeenth Century who are key characters in my works, buy my novels, give me direct feedback – or book me to talk to your group about one of the many subjects close to my heart.

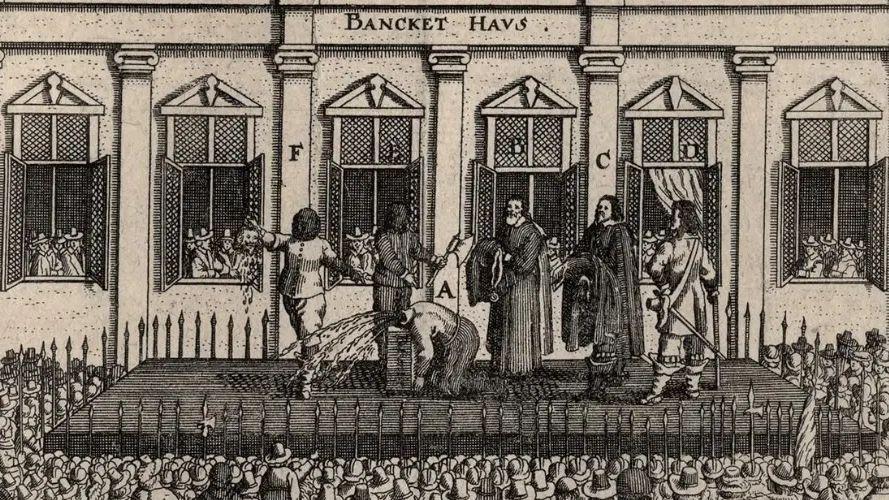

EXCLUSIVE EXTRACT FROM REGICIDE, THE THIRD INSTALMENT IN THE ACCLAIMED HACKER CHRONICLES SERIES

Britain is drawn into another bloody war

Introducing Francis Hacker – husband, father, soldier and spy

The squire who fought for a cause he'd willingly die for

At the outbreak of hostilities in August 1642, Francis Hacker was just one of many members of England's landed gentry who supported attempts by Parliament to hold Charles the First to account. He was a man of few words, preferring deeds to oratory. Yet even though he was a quiet and introverted figure, Francis inspired loyalty in the troops he led – and proved to be an extremely capable military commander, catching the eye of Oliver Cromwell and other leading Parliamentary figures.

Introducing Lucy Hay, the Countess of Carlisle

A beautiful spy whose betrayal fuelled civil war

She was feted by poets and nobility alike, yet none knew of the dangerous games played by Lady Lucy Hay, one of England's most beautiful women who resided at the Court of King Charles. For Lucy was a Parliamentarian spy, and a confidante and friend to Queen Henrietta – an association that helped her undermine the King's desperate attempts to capture five prominent Parliamentarians who led opposition to his unpopular, divisive and ultimately terminal reign.

1642-51: the bloodiest period in British history

The three British civil wars pitted brother against brother, ripped families and communities apart – and resulted in more than four per cent of the total population of England, Scotland and Wales being slaughtered. Relations between the King and Parliament had been deteriorating since the rule of King James the First. When he died in 1625, and Charles, his eldest surviving son, became King, relations between the crown and the people dipped to a new low. But rather than listen to the restraining voice of Parliament, the King continued to pursue his own domestic and foreign policies that would lead to his ultimate downfall. Disastrous miscalculations, such as the levying of the hugely unpopular 'Ship Money', the imposition of 'popist' religious practices on the Scottish church and several embarrassing and costly military failures, left the King and Parliament at loggerheads with one another. Increasingly, neither would cede ground to the other.

By 1642, matters had become so bad there could only be one outcome... Civil war was declared on 22 August 1642, when the King raised his standard in Nottingham.

Nine years of bloody warfare ensued, during which time Charles lost his throne and head, Oliver Cromwell became the most powerful commoner in British history, and Francis Hacker – a Leicestershire landowner and gentleman – rose from obscurity and became one of the New Model Army's finest commanders.

Introducing Prince Rupert, the King's eccentric nephew

From Europe's killing fields came a Bohemian Prince

Underneath the ornately crafted clothing and the perfumed wig, Prince Rupert of the Rhine was a man of steel who enjoyed a well-earned reputation as a formidable leader of men – earned on the battlefields of Europe during the merciless Thirty Years' War. A nephew to King Charles, Rupert was held in awe by the Royalist troops he commanded, who revered his bravery and military shrewdness. His enemies, meanwhile, feared and loathed him, often blaming him for committing some of the bloodiest atrocities committed on British soil.

Introducing Oliver Cromwell, the man who would define an age

The formidable soldier whose deeds would divide a nation

Oliver Cromwell's name continues to provoke a reaction hundreds of years after his death. You are either for him, or against him: there is little room for manoeuvre in between! Yet what most people believe Cromwell stood for is often based on misperceptions and factual inaccuracy. Yes, he was a formidable soldier and military leader. And yes, he held strong religious beliefs. But he was also a sensitive man whose main purposes were to hold a wayward King to account – and seek important Parliamentary reforms.